Dear Neighbors,

For

many years, the work of caring for older people and young children has

faced an increasing crisis as there are just not enough people willing

to do the work for the low pay. The Boston Foundation's Boston

Indicators and Skillworks released an extremely important report on that workforce; last week, the Caucus of Women Legislators hosted a presentation on it. For

many years, the work of caring for older people and young children has

faced an increasing crisis as there are just not enough people willing

to do the work for the low pay. The Boston Foundation's Boston

Indicators and Skillworks released an extremely important report on that workforce; last week, the Caucus of Women Legislators hosted a presentation on it.

The report shows the historical roots of this problem and emphasizes the

injustice of undervaluing this work. It signals that the Boston

Foundation, with its credibility and influence, sees the issue as an

urgent one of racial and gender justice.

This newsletter is a shortish summary, along with ideas and information

from my work as chair of the Elder Affairs Committee. I hope you will

read the full report, and push for solutions to the problem of low wages and work shortage in these crucial - yes, essential - jobs.

Andre Green, Director of SkillWorks and

chair of the Somerville School Committee, introduced the report at the

Women's Caucus briefing. He has said, "If we paid jobs according to

their value to society, child care workers, home care workers and

long-term care workers would be at the top of the scale. But too often,

we determine our pay scales not by what the job is, but rather by who

does it. COVID underscored the essential nature of care work – the

question now is whether we are willing to acknowledge and value that

essential nature with higher pay and better working conditions.”

Historical Roots of Undervaluing Caregiving

Until the Industrial Revolution, care of

children and people with disabilities was mostly done by women at home.

Wealthy white women were able to perform culturally valued roles like

hostessing parties and directing servants, while laundry, cleaning, and

other "dirty work" were off-loaded onto enslaved Black women and other

lower class women.

As white women moved into the labor force in retail and clerical jobs,

women of color were "channeled into domestic labor." Labor reforms of

the twentieth century excluded most care workers. Home care workers were

only included in federal minimum wage and overtime protections in

2015; Massachusetts passed the Domestic Workers Bill of Rights just the

year before.

Increased Need for Workers

People are living longer, and surviving longer with disabilities. US life expectancy rose from 47 years in 1900 to nearly 79 years in 2019 - though it has actually fallen since, and was 76 in 2021, due largely to COVID and opioid overdoses. People are living longer, and surviving longer with disabilities. US life expectancy rose from 47 years in 1900 to nearly 79 years in 2019 - though it has actually fallen since, and was 76 in 2021, due largely to COVID and opioid overdoses.

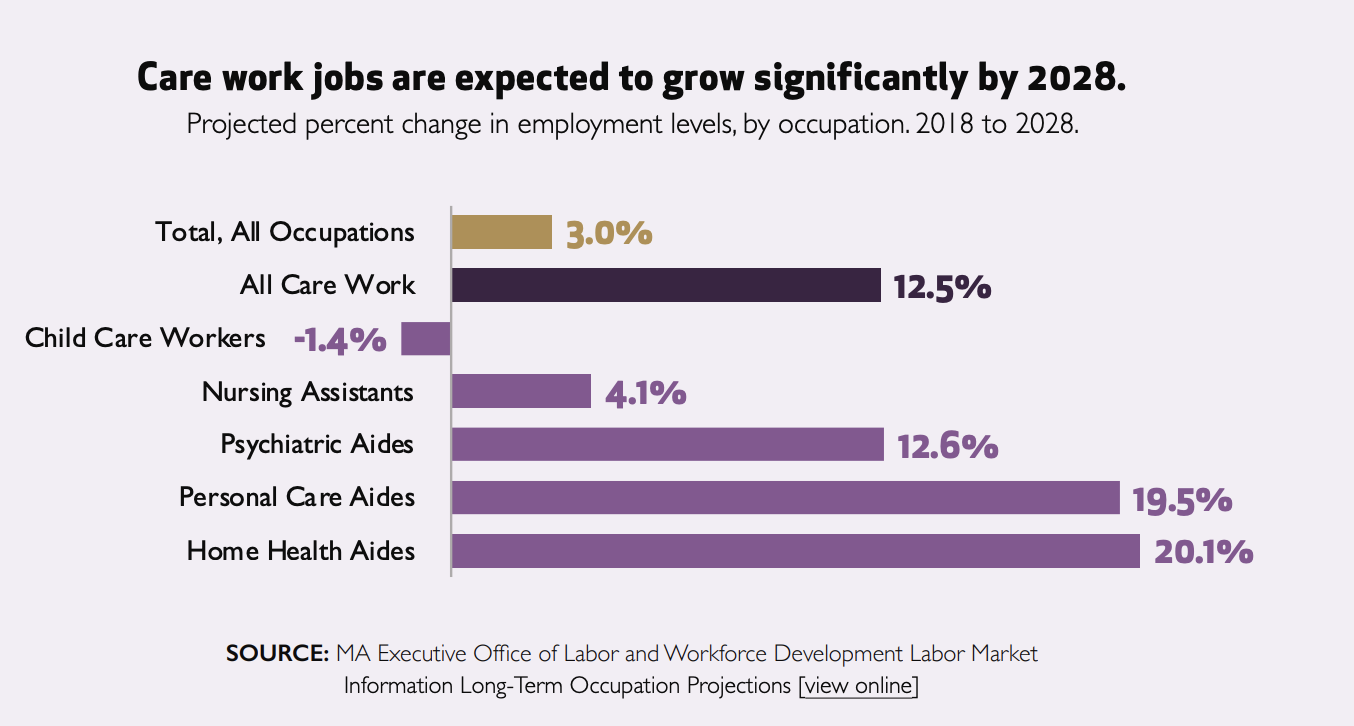

Not surprisingly, the need for careworkers is expanding. These are now the fastest-growing jobs in the workforce.

But home care agencies, nursing homes, and child care centers can't find

nearly enough workers to fill those jobs, which means many people

aren't receiving services they need, and families can't get the care

that would allow them to work.

The Effect of Worker Shortages

Right now, there are close to 5000 older people who qualify for public home care services, but who aren't receiving them because of a shortage of workers.

Right now, many hundreds of patients are in hospitals waiting to be discharged to nursing homes that can’t accept them because of staff shortages. Nursing homes report

a shortage of 6700 nursing positions and 1700 non-nursing positions.

As a result, more than half have limited their admissions.

19% of child care programs closed permanently during

the pandemic, Most remaining ones are short staffed and and almost a

quarter of them lack enough staff to enroll the number of children

they’re licensed to serve, according the the Mass. Department of Early Education and Care.

This is particularly true in centers that serve low income people and

families of color, so those parents have a harder time working.

Who are the Caregivers?

.

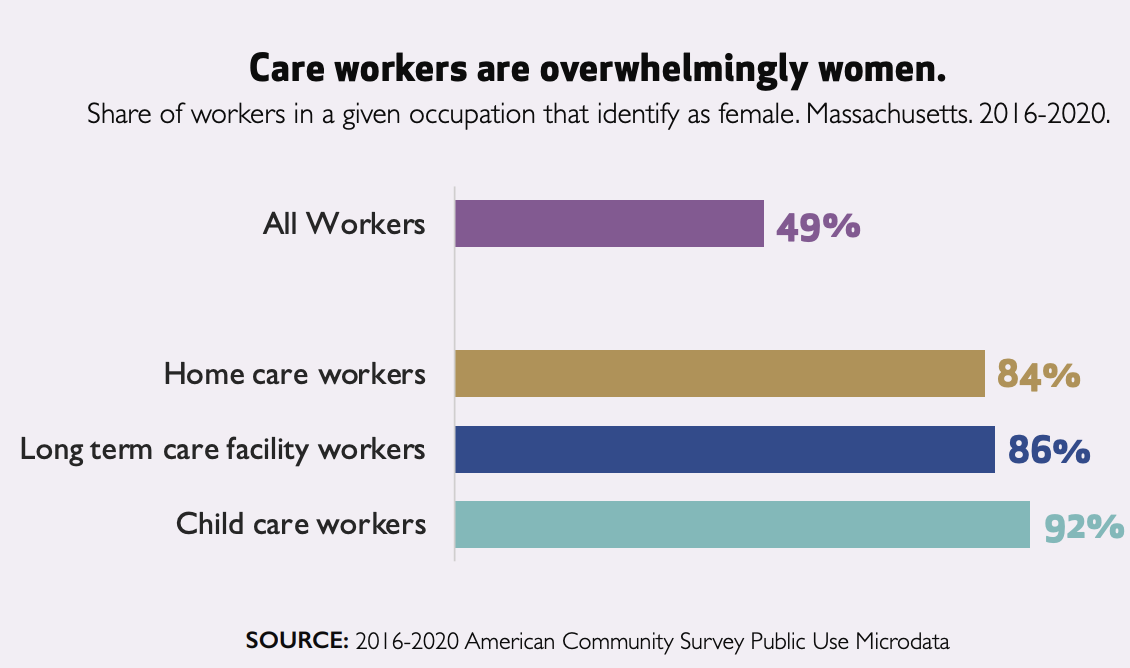

Caregivers are overwhelmingly women, and disproportionately people of color.

The report notes that "The vast overrepresentation of Black workers in

home care and long-term care facility work reflects the long history

described earlier of racial and gender discrimination that has relegated

Black women to the most physically taxing direct care."

Low pay causes shortages

Direct care workers do crucial work, and were celebrated as essential workers during the early pandemic. But their wages are

near the bottom of all occupations. The chart shows that they earn a

little more than half the average hourly wage. The chart is for

2016-20; wages have gone up, especially due to the state minimum wage

increase as well as ARPA funds dedicated to temporary Medicaid rate

increases. Direct care workers do crucial work, and were celebrated as essential workers during the early pandemic. But their wages are

near the bottom of all occupations. The chart shows that they earn a

little more than half the average hourly wage. The chart is for

2016-20; wages have gone up, especially due to the state minimum wage

increase as well as ARPA funds dedicated to temporary Medicaid rate

increases.

Wages in nursing homes are now closer to $18 per hour.. Personal Care

Assistants (PCAs) in Massachusetts are unionized and recently bargained

for a minimum wage of $17.75. Pay increases have not kept up with

inflation, especially in housing

Due to the Grand Bargain of 2018, the MA minimum wage will increase to $15/hour in January. This is the last year of the phased increase to "Fight for Fifteen." Tipped employees' minimum employer pay will be only $6.75 and premium pay for Sundays and holidays will end. Farmworkers, fishermen, and

some other occupations are still not protected by overtime provisions.

Plenty of legislative work needed, as I've learned as chair of Labor

and Workforce Development.

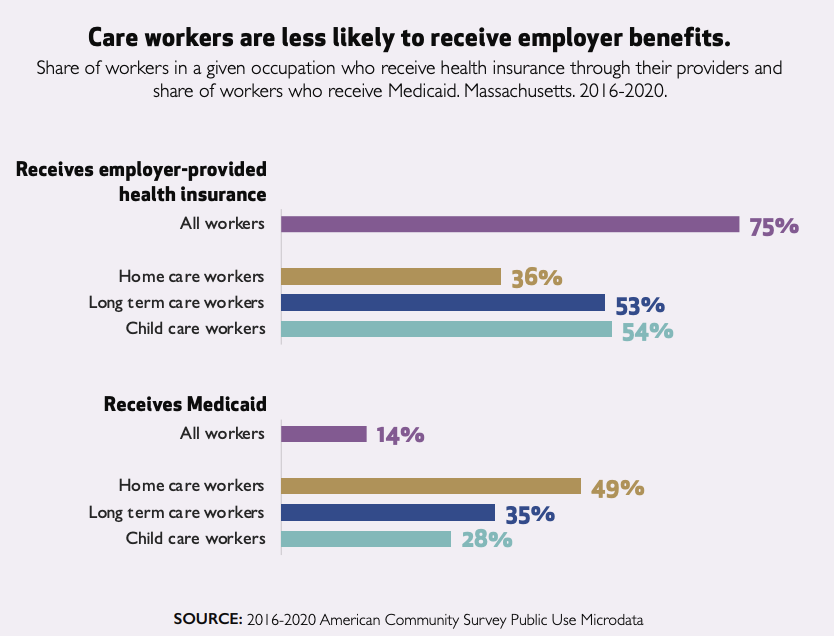

Careworkers

are also much less likely to receive employer-paid health insurance and

far more likely to rely on MassHealth (Medicaid). They are more likely

to qualify for SNAP (food stamp) benefits. This means that if they manage to work enough hours they will hit the cliff effect and lose benefits. Careworkers

are also much less likely to receive employer-paid health insurance and

far more likely to rely on MassHealth (Medicaid). They are more likely

to qualify for SNAP (food stamp) benefits. This means that if they manage to work enough hours they will hit the cliff effect and lose benefits.

They are also less likely to have pension plans: 35 percent of the total

workforce has a pension or other retirement plan (we all need one, even

with Social Security) compared to just 10.2% of child-care workers and

12.6% of home care workers. This means that the workers who are poor

now because they care for older people will be even poorer when they

themselves retire.

Poor job quality adds to shortage

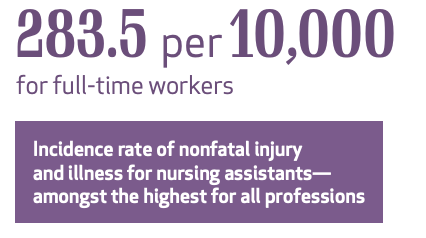

These

jobs are often very physically and emotionally stressful. Nursing

assistants have one of the highest injury rates of any job. Home care

workers have erratic schedules, and may not be paid if their client is

sick and cancels service. Having to care for several clients a day

means they may have unpaid travel time (despite the law) and are more likely to be exposed to COVID and other dangers. These

jobs are often very physically and emotionally stressful. Nursing

assistants have one of the highest injury rates of any job. Home care

workers have erratic schedules, and may not be paid if their client is

sick and cancels service. Having to care for several clients a day

means they may have unpaid travel time (despite the law) and are more likely to be exposed to COVID and other dangers.

Low pay and low job quality lead to high annual turnover

rates of over 30 percent in child care and up to 128 percent in nursing

home workers. Turnover, of course, means that workers have less

training and experience, and are less able to provide excellent care for

vulnerable people.

Reduced immigration adds to shortage

Caregivers

are more likely to be immigrants, including almost half of nursing home

workers. The report notes that "Immigrants, particularly immigrants of

color, drove Greater Boston’s population growth between 1990 and 2019,

accounting for almost 90 percent of net population change during that

period. Slowing immigration during the Trump administration combined

with international travel restrictions during the pandemic have led to

declining immigration rates in recent years." Caregivers

are more likely to be immigrants, including almost half of nursing home

workers. The report notes that "Immigrants, particularly immigrants of

color, drove Greater Boston’s population growth between 1990 and 2019,

accounting for almost 90 percent of net population change during that

period. Slowing immigration during the Trump administration combined

with international travel restrictions during the pandemic have led to

declining immigration rates in recent years."

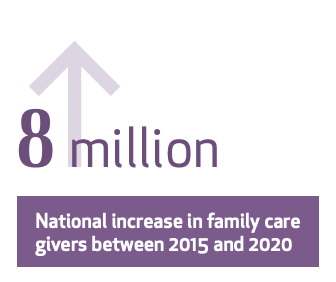

Unpaid Caregivers Provide More Care

Family members provide many hours of unpaid care for both children and older people who need help. Mass. Caregivers Coalition

estimates that pre-pandemic there were 844,000 unpaid family members

caring for older relatives, of whom more than 600,000 were also

employed. Some of these people are part of the sandwich generation,

caring for parents and children at the same time. Family members provide many hours of unpaid care for both children and older people who need help. Mass. Caregivers Coalition

estimates that pre-pandemic there were 844,000 unpaid family members

caring for older relatives, of whom more than 600,000 were also

employed. Some of these people are part of the sandwich generation,

caring for parents and children at the same time.

As more people live longer and hope to age in place, these caregivers play an important role. Innovations such as "hospital at home"

offer many benefits but often require someone to be available to help.

But the cost in lost income and stress can be significant. The report

says that "affordable child care would lead to an increase of over

$100,000 in lifetime net income for Black mothers, the highest of any

racial or ethnic group."

Solutions?

The report recommends policy changes to improve care workers' job quality:

- continue to raise the minimum wage

- license home care agencies

- strengthen career ladders

- expand the Earned Income Tax Credit to unpaid family caregivers

- improve care workers' ability to unionize

We

can also provide free training and incentives to join this workforce.

An important reform Mass. Home Care and others have sought for years

would be to allow spouses to be paid as caregivers

by MassHealth. 15 other states allow this. This is one of many

proposals for long term care we hope the legislative leadership will

prioritize and the new Healey-Driscoll administration will embrace in

the new year. I am encouraged by the formation of Dignity Alliance Massachusetts, which brings together groups and advocates to push for more focus on the needs of older adults.

In

solving the crisis in caregiving, there is absolutely no substitute for

more money, and for higher pay. Since the state funds so much of the

nursing home, home care, and (less so) early care industry, it will take

a lot more of the state budget. It will mean, in my opinion, being

willing to ask the people and companies who have seen great increases in

their wealth to contribute more to build a more just economy and

society. Everyone, rich and poor and middle class, will benefit when

these essential workers are paid a fair wage, and there are enough of

them to serve all of us.

Stay safe and stay in touch,

|

0 comments:

Post a Comment